Publisher’s Note: This is a guest post by Aaron Kuehn. Aaron is a former chair of BikeLoud PDX, is passionate about wayfinding, and wrote a series of articles for BikePortland on bikeway design.

Early Sunday morning, as the springtime sun warmed the asphalt, a group of nearly 20 curious Portlanders, planners, and advocates gathered in hi-viz vests to roll up their sleeves—and then roll through a notoriously treacherous intersection at SE 7th and Sandy.

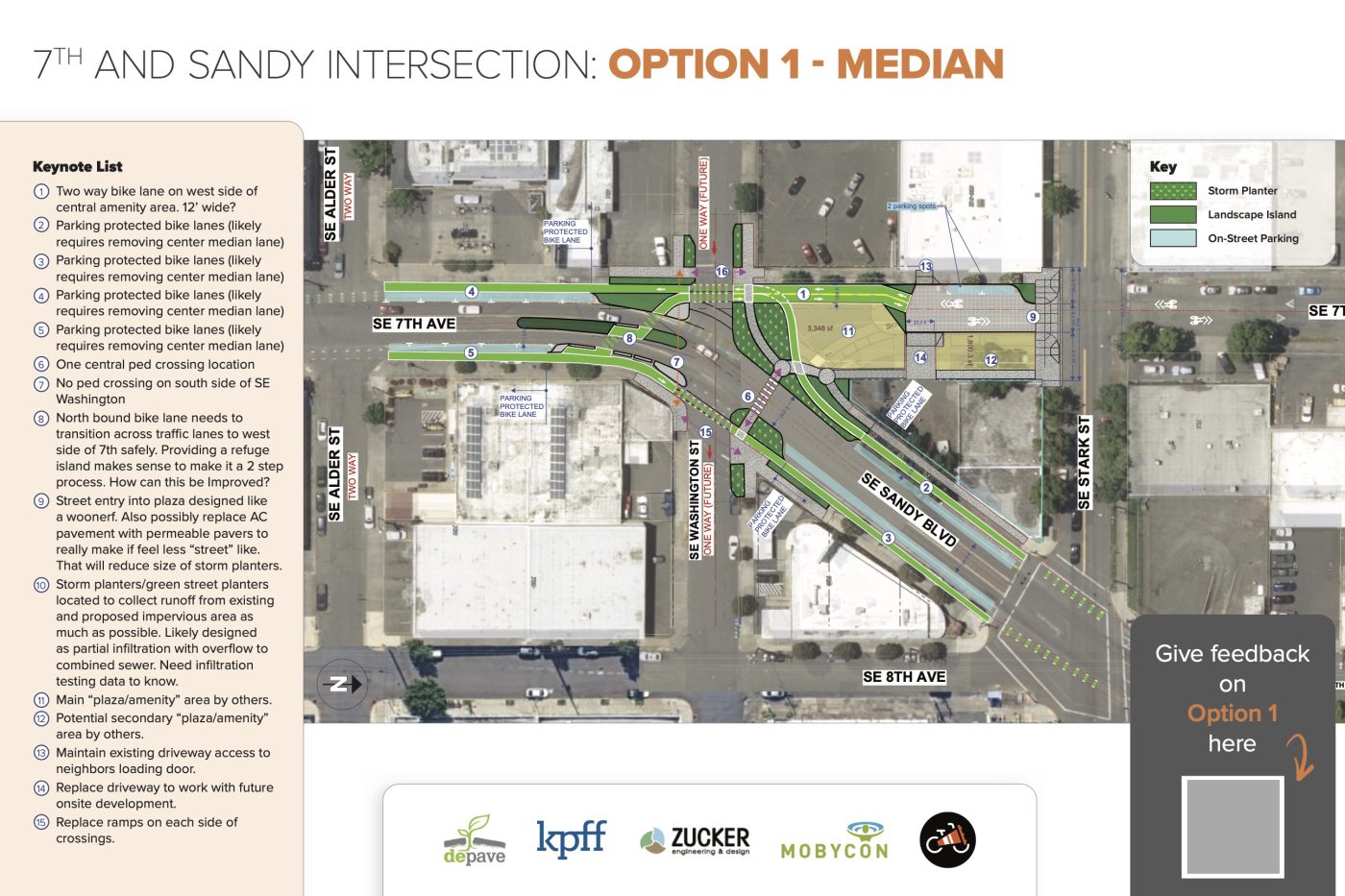

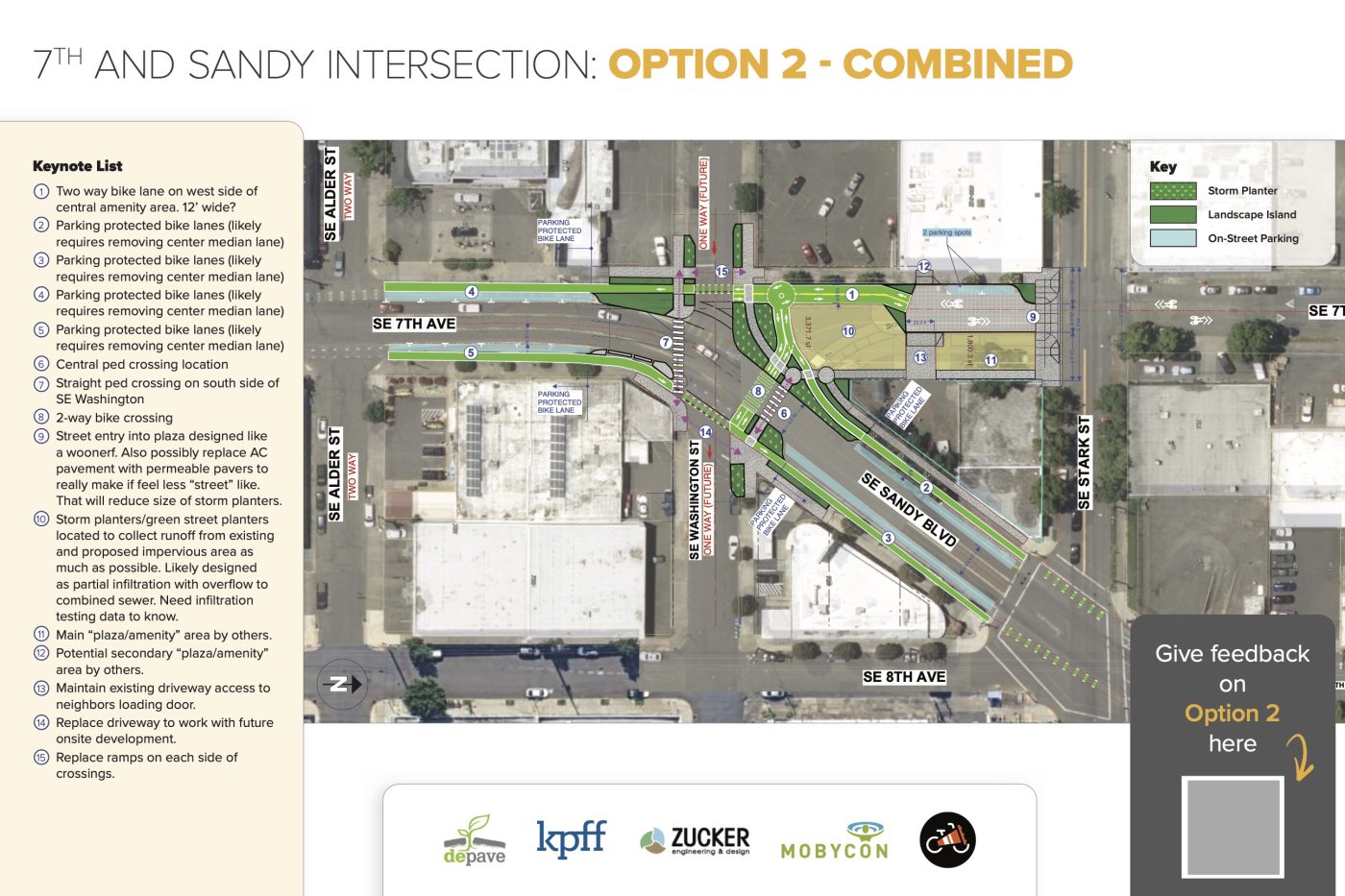

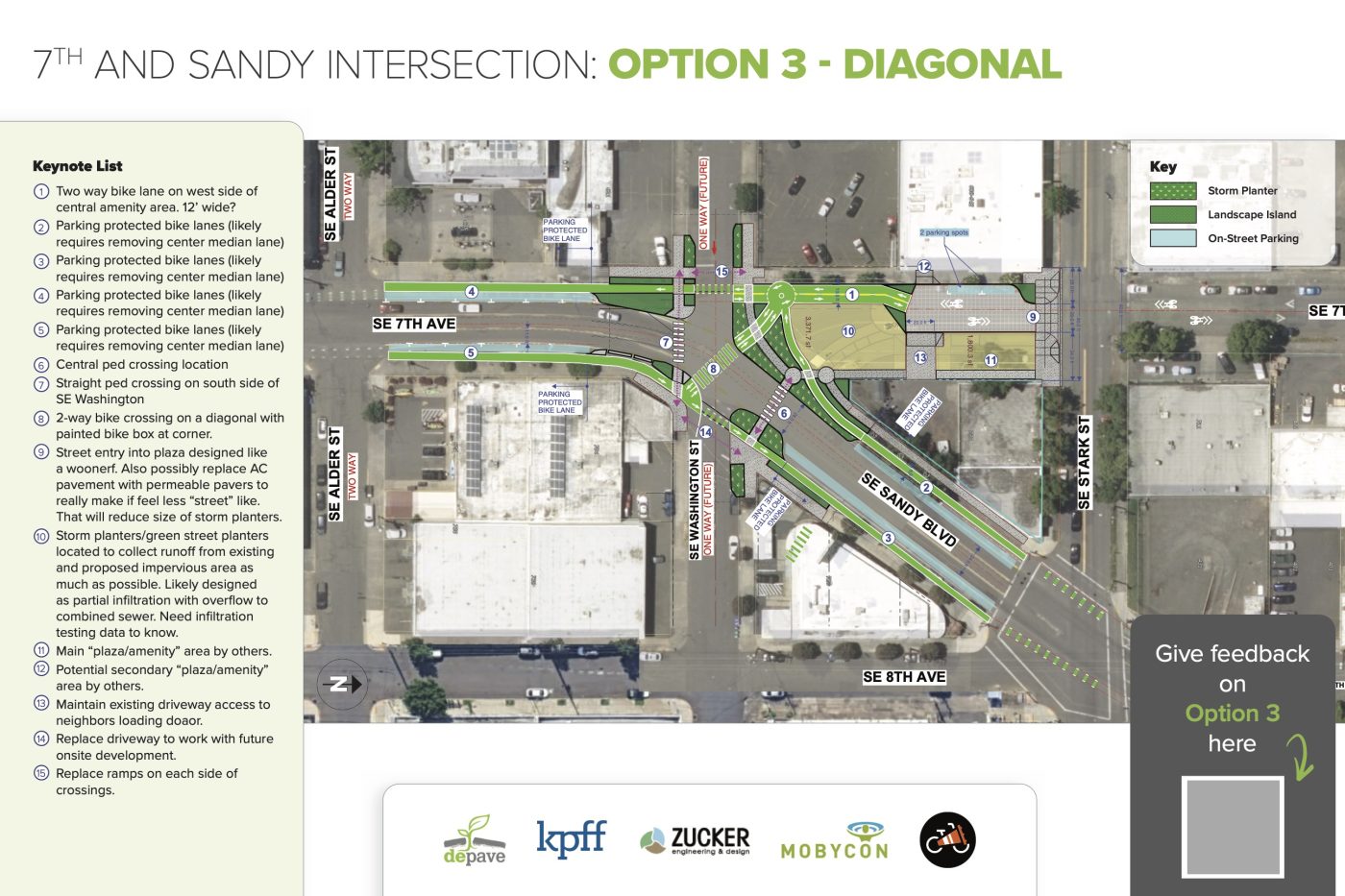

The event, listed on the Shift calendar as the Street Plaza Test Ride, was no ordinary community feedback session. Instead of just viewing plans on a board, participants took part in a live-action, hands-on “planning by doing” process: sketching new lanes, medians, and turn boxes with tape and cones, then test-riding different configurations to feel what worked best. The goal? Refine bikeway design options for a challenging five-way intersection that’s both a pivotal link in the 7th Ave Neighborhood Greenway and part of an evolving public plaza.

This area has long been a sore spot for people on bikes. In a 2023 BikePortland article, Taylor Griggs described SE 7th and Sandy as a “sketchy intersection,” where crossing Sandy northbound means darting across multiple lanes of fast-moving car traffic with limited visibility. “It’s one of the most complicated maneuvers I regularly make,” she wrote. “I dread the experience every single time.”

Over the past few years, ongoing efforts have aimed to reimagine this space—not just for safety, but for public life. Depave’s 2022 block party previewed the potential of a people-centric plaza, and more recently, a BikePortland video in 2024 highlighted last summer’s creative reuse of space—and lingering concerns from riders about the safety and comfort of the temporary bikeway winding through it.

Sunday’s test-ride event built on all of that, bringing a new level of focus and nuance to the conversation. It was led by a unique collaboration: the nonprofit Depave, now in its fourth year of iteration on the plaza; Adam Zucker, an engineer who previously developed a landscaped plaza nearby; Mobycon, a Dutch firm known for high-quality bikeway planning; engineering consultants KPFF; and BikeLoud, the grassroots advocacy group that helped organize and facilitate the ride.

Importantly, the most recent design options were drafted by KPFF and Mobycon, and the on-the-ground feedback session was led by me on behalf of BikeLoud. After completing a heatmap-style study showing that people on bikes mostly use the shortest path to cross the site, biking this stretch myself multiple times per week, and seeking the next breakthrough in community-focused planning and design, I felt it was important that this exercise be driven by action-oriented planning: an underutilized method that trades static renderings for real-world testing, especially when the stakes are high and the space is complex.

And this site is very complex. It’s not just the five-way geometry, but the steep grade, the blind turn, the vehicle speeds, and the mix of travel modes that make this a crucial test case. It’s also a space in transition—from redundant roadway to public plaza—meaning that transportation and placemaking need to coexist, not compete. For other plazas in Portland and future segments of the Green Loop, this type of engagement could be a model.

The conversations on the pavement were practical and cooperative. Volunteers debated the best turn angles for visibility and lane placements. Some emphasized the need for more direct routes for vehicular cycling; others focused on how to make the Sandy crossing intuitive and reassuring for all users. Everyone brought a valuable lens: riders who use the intersection daily, planners steeped in Dutch cycling infrastructure—even freight operators like B-Line Urban Delivery are invested in the bikeway and the plaza’s success.

The design team is reviewing the feedback collected that day and will use those observations to shape the next temporary buildout of the plaza, scheduled to open August 9 through September 19. Hopefully, Depave will secure the additional funding needed to finally build the plaza using permanent materials—and by that time, the design will have been thoroughly tested through all these trials.

Yes, action-oriented planning can take more time and resources than traditional methods—but it also surfaces better ideas. When people test out designs in real life, they give more useful feedback. They notice things you can’t see on paper. They revise. And they come away with a sense of shared ownership. There were some regrets expressed that this design approach wasn’t used at other complex junctions in the bike network—but also hope that it might be going forward.

As we packed up cones, barriers, and rolls of four-inch white duct tape at the end of the day, there was a feeling that something important had happened—not just for this intersection, but for how we approach street transformations more broadly. We didn’t just talk about best practices. We created them as we pedaled. Together.

—

Want to help shape future designs at SE 7th and Sandy or other locations? Keep an eye out for upcoming test rides and plaza events. And if you have thoughts about this intersection or ideas for balancing bike access with public space, add your comments below.